When looking at overall contribution to bridge, as a player, director, team captain, system theorist, teacher, mentor and administrator, there is no doubt that Bill Schaufelberger (1902-72) was the dominant figure in bridge in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s.

When looking at overall contribution to bridge, as a player, director, team captain, system theorist, teacher, mentor and administrator, there is no doubt that Bill Schaufelberger (1902-72) was the dominant figure in bridge in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s.

As a player Bill first began to rise to prominence in 1936. In 1937 he and his partner, EO Harris dominated the major NSW pairs events. When Les Longhurst was unavailable, he became part of the NSW team, playing with Frank Cayley, which beat New Zealand in the 1937 challenge match. He was again a member of the NSW team in 1946 when the national championships resumed after the war and from that point he was captain of the NSW team at the ANC every year (except 1953 when he was asked but unavailable) between 1947 and 1957, and again in 1961.

On nine of the eleven years, in which he captained the team, NSW won the interstate – a record that is unlikely to be bettered. He twice won the Australian Open Pairs – the inaugural event in 1954 with Time Seres and in 1958 with Frank Cayley. He was captain of the first Australian international team that competed at the Turin Olympiad.

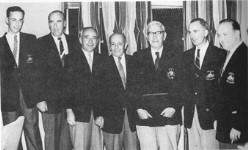

The Australian team at the 1960 Turin Olympiad. From left: Dick Cummings, Bob Williams, Sam Bridgeman, Bill Schaufelberger, MJ Sullivan, Hal Oddie, Tim Seres.

Partly for health reasons, Bill played relatively little competitive bridge from the 1960s onwards but at the time of his death, he still had the third highest number of masterpoints among Australian players.

In 1948, Bill was the highest ranked NSW player by a considerable margin. The hands that survive seem to show that he was an absolute master of the art of playing as if double dummy – identifying possible distributions and using them to his advantage. As with many great players, a distinguishing feature of his play was to eschew finesses that nine out of ten players would take without a thought.

In the 1949 national championships, Bill, playing North, gave NSW a big swing against Queensland on the following hand.

| ♠AQT84 ♥65 ♦Q93 ♣AJ8 |

||

| ♠J ♥KQT9872 ♦JT4 ♣93 |

♠32 ♥43 ♦A872 ♣QT542 |

|

| ♠K9876 ♥AJ ♦K85 ♣K76 |

Playing in 4S, Bill won the ♥K lead and played two rounds of trumps and then exited a heart to West. West returned a club and after taking the ♣K and ♣A, Bill threw East in with his third club. East is now end-played. A club return gives a ruff and discard and a diamond lead sets up two diamond tricks.

Bill was a very strong proponent of the importance of thought at tricks one and two. In this hand from the 1950s, Bill, playing rubber bridge was dealt:

♠AKQT987

♥A43

♦AK

♣A

Bill, with visions of a grand slam, opened what was in his system a forcing strong 2S. His left hand opponent overcalled 4H, and the rest of the auction having not really clarified to his satisfaction what could be done about the heart losers, Bill, feeling he was being a bit timid, settled in 6S.

The lead was the king of the clubs and dummy was:

♠J2

♥2

♦6543

♣765432

Fortunately, West had no trumps to lead. However, there is still a chance for declarer to go wrong. After winning with the Ace of clubs, many players will play the Ace of Hearts, hoping to follow with a small heart ruffed by the Jack. However, on this hand, West had overcalled with 9 hearts and the Ace of hearts would have been ruffed, a spade would have been returned and the contract would go one down as declarer will be stranded with a second heart loser. Bill saw this possibility and made the counter-intuitive but fool-proof lead of the three of hearts at trick two. After giving up this trick, nothing can touch the contract. His remaining small heart can be ruffed by the jack of spades and the ace can be played after trumps have been cleared.

Another par point competition hand from the early 1950s showed the same sure hand.

North

♠Q3

♥AKQ97

♦A432

♣43

South

♠A4

♥JT8432

♦ 5

♣AKT2

The challenge given was to make seven hearts on the lead of the QC. Bill’s commentary was that “all that was needed was correct timing and not play a trump trick at trick two but play a dummy reversal by ruffing diamonds immediately. Not forgetting to cash your ace of spades to make the Q of spades the threat card. After ruffing three diamonds and crossing three times to the big trumps in dummy, the final position was:

| North ♠S Q ♥H 97 ♦D – ♣C 4 |

||

| West ♠KJ ♥ – ♦ – ♣J9 |

||

| South ♠4 ♥- ♦- ♣AT2 |

On the last two trumps from dummy, the 4 of spades and the 2 of clubs were discarded. West was thus hopelessly squeezed.

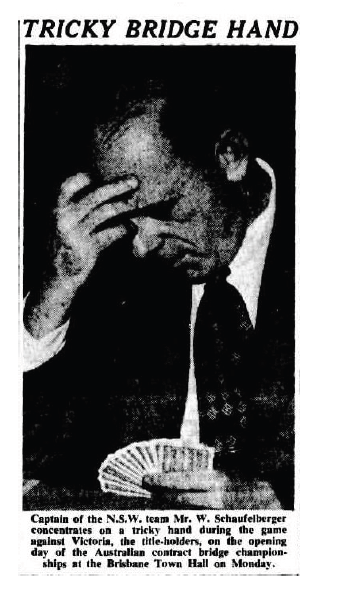

As a player Bill was renowned for his concentration and at times associated obliviousness to his surroundings, much like Terence Reese. His wife Greta recalled that “one evening I went to the club to speak to him. He got up from the table, but walked straight past! I had to stop him and say. “May I introduce myself, I am Mrs Schaufelberger.”

His intense concentration at the bridge table was accompanied by a correspondingly high level of absent-mindedness in other matters. Cathy Chua relates an anecdote from Maurice Goldstein, the top English chess player and later NSW bridge representative, who recalled Bill gratefully accepting a lift home, only to remember on arrival that he had parked his car outside the Sydney bridge club.

Bill’s contribution to bridge went well beyond his own play. Crucially, he was responsible for bringing along a number of the players who dominated Australian bridge in the sixties and seventies and beyond – including Tim Seres, Denis Howard, Dick Cummings and Roelof Smilde – who were often invited to Bill’s home. He immediately spotted the talent of Tim Seres when he first turned up at the Sydney Bridge Club, observing that while he knew next to nothing about bidding but was a genius at card play. The two played extensively as a pair from 1948 to 1960.

Seres always acknowledged his debt for the early lessons he got from Bill and wrote in tribute that:

I could not have asked for a better partner. Our styles blended perfectly; he was unruffled by my vagaries, but sound as a rock himself, with a card-playing technique that one could only envy. One of the richest rewards in bridge is to have a long-standing partnership with a really good player. On that account I will always be in Bill’s debt.

Seres often spoke in later years of Bill’s unruffled nature and his wizardry in playing 1NT contracts.

Unlike many players of the era, who had little interest in bidding as opposed to the play of the cards, Bill was interested in innovation and international developments in bidding . He made substantial contribution to theory, in particular the development of the New South Wales System. This was first published in 1948, with the proceeds going to the NSWBA. In his introduction to the second edition of The New South Wales System (1970), editor Denis Howard wrote “Historically, the System has been moulded by two groups. Originally devised by Longhurst, Makai, Shaufelberger, Verne and Williams, the System was virtually unchanged until the late nineteen fifties. From that point onwards custody passed to the second group, Cummings, Howard, Seres and Smilde, with Schaufelberger as the unifying link”.

The system was based on a mixture of different systems that appealed to Bill and the others involved, including both Culbertson and the Vienna System that had been invented by Paul Stern of the Austrian team before the war. When first played in 1947, it included the short club, showing hands lacking a five card suit other than clubs and the 1NT which showed a strong hand of any distribution. Opening values were based on Culbertson honour trick counts and the system included low level asking bids. After 1947, the 1NT bid was abandoned in favour of the normal balanced 16-18 opening and a 1D bid could show 4 of the suit. In its mature form, the two level bids were as follows: 2C = 23+ game force any shape, 2D =21-22 balanced, 2H/S were weak and 2NT was 15+ with both minors.

As a mentor and a captain, Bill’s concerns went beyond technique. Bill was used to being in charge, did not have, either as Director or Captain, what might be called a sunny personality, and was not afraid to lay down the law to his team-mates. Les Longhurst recalled, for example, being told that there was to be no gloating over opponents and that any player found doing this would be benched. He was averse to anything that might seem self-congratulatory and not afraid to dish out some tough love in this regard if he thought the person could take it. Paul Lavings remembers a story from Bill’s later years as chief director of the NSWBA in the late 1960s, when it was on the corner of George and Grosvenor Streets near Circular Quay. Paul proudly approached Bill and told him that he had just successfully pulled off a triple squeeze – “so what?”, came the dry response.

Although great rivals, relations between Bill and Victor Champion were characterised by great mutual respect. When NSW won their first championship, Bill commented to Les Longhurst that he was glad that Champion had been playing for Victoria, as otherwise they would not really have proved that they were the best. When Victoria finally won back the Championships in 1951, the History of Australian Bridge records that Bill presented the cup to the Victorian team, joking that it ‘had been left in his care (temporarily) by Mr Champion in Sydney in 1947 with strict instructions to guard it carefully, not parting with it to anyone until required again by Mr Champion himself.’

Personal Life

Bill, full name, Willy Karl Arthur Shaufelberger, was born in Zurich, Switzerland, on 25 October 1902, into a wealthy business family. We have no information on his early life other than that he qualified in Zurich as an accountant, did his army service in Switzerland and was enlisted in the reserves as a machine gunner. He came to Australia in August 1925, apparently on the recommendation of a friend who operated a sporting goods business. His first home in Australia was (ironically, given his later role in ending Victorian dominance) in Melbourne. His passport listed his occupation as businessman and he had a share in the friend’s sporting goods business but in this first period he also worked as Secretary to the Swiss Consul and Nestle as an accountant.

While in Melbourne he married Phyllis Jean Cattanach of South Yarra, whose father, AR Cattanach was Principal of the Prahran Technical College and a leading figure and innovator in the fields of adult and technical education. In April 1928, he and Phyllis visited Switzerland for a year, probably associated with Bill’s involvement in family business and after returning briefly to Australia, moved to England in July 1930.

They did not come back to Australia until February 1934. We do not know anything about their time away, except that it was longer than they wanted. Bill had not previously arranged a re-entry permit and this had never been a problem before – but the tighter conditions of the early thirties meant years of lobbying before he and Phyllis could get back in. Phyllis was Australian-born and had been an Australian citizen at the time of her marriage. However, under the law of the time, she lost her Australian citizenship on marriage and was also unable to return.

Loss of citizenship by women on their marriage was an issue of concern to many in the 1920s and 1930s. It was very common practice internationally for a woman to lose her citizenship when marrying a foreigner. Sometimes, depending on local law, this meant that she gained citizenship of her husband’s country but not infrequently, the woman became stateless. At the instigation of activists on the issue, it was discussed at a number of international forums. In general, Australia’s approach before and immediately after the second world war tended to be somewhat two-faced – voting for reform at international meetings but leaving its own legislation unchanged.

After the war, the situation in Europe and potential loss of citizenship, became a major issue for women considering marrying men whose home countries were in a very bad situation or under communist control. The fiancée of the Victorian state representative, Edgar Mohl, faced a similar situation.

Australia finally changed the law to allow women marrying foreigners to retain citizenship in 1946 and in 1948 created full gender equality in the law.

Bill and Phyllis returned to Australia in 1934 but this time to Sydney. It is likely that Bill’s father had died and, having been quaintly described in the visa applications as having ‘great expectations’ he was now recorded to be of ‘independent means’. He is first recorded as playing bridge in 1935 with his brother-in-law, Alan Cattanach, who was a very capable player and winner, with his wife, of the 1935 Australia and New Zealand Olympic competition.

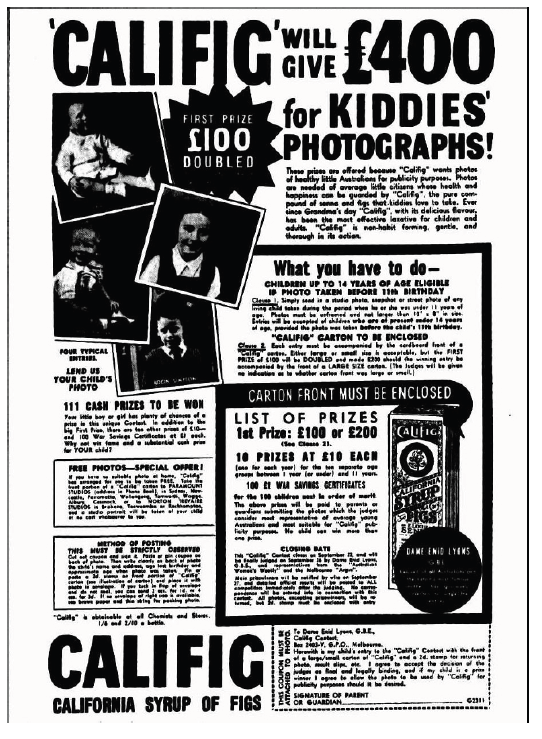

In Sydney, he invested in Paramount Studios – not the Hollywood variety but a chain of photographic studios. Bill seems to have been an astute businessman and, in a time when camera ownership was not so widespread and demand for formal photos high, these flourished with the help of aggressive advertising and special offers.

In Sydney, he invested in Paramount Studios – not the Hollywood variety but a chain of photographic studios. Bill seems to have been an astute businessman and, in a time when camera ownership was not so widespread and demand for formal photos high, these flourished with the help of aggressive advertising and special offers.

Bill was one of the pioneers of the cross-advertising gimmick. In one campaign, which is a tribute to the state of the Australian diet of the time, parents who had their children’s photos taken were offered the opportunity to win £100 and have their child be the poster boy or girl for advertising the popular laxative, Calific.

Phyllis Schauffelberger died in 1937 and Bill, probably for a combination of personal and business reasons, returned to Europe between April and November 1938. Bill became a citizen in 1939. Foreign residents were not encouraged to take up citizenship as is the case now and the process required Bill to place an advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald so that any objections could be recorded and he was vetted by a team of two officials who interviewed referees. The elite nature of the bridge world meant that Bill was not short of prominent advocates. His main referees were the Parliamentary Draftsman, Edward Cahalan and Hubert Millingen, a prominent businessman and husband of the pioneering bridge author, player and teacher, Myra Millingen who had died in 1936. The officials’ final verdict was the Bill ‘seems a good sort’ and his citizenship was approved.

His immigration worries were therefore over but his family and personal life continued to be something of a window into the murky state of immigration requirements in the 1940s and early 1950s. During his return to Europe after his first wife’s death, he met Margaret (Greta) Schaffer in Vienna and in 1939, narrowly before the beginning of war, brought her back to Australia. They married in July 1939. It is clear that Bill assumed that Greta automatically gained citizenship by marrying him in the same way that she automatically lost her German citizenship. However, the rules were that she was required to apply and there was a small time window for the citizenship to be granted more or less automatically because of marriage. Otherwise the normal lengthy process applied. The fact that Greta was not a citizen was discovered only later. Lobbying and legal intervention got a waiver of the requirements but it was again a reminder of the fragile position of married women.

Bill’s history also brought to light another little known aspect of Australia’s past immigration policy. After the war, he also applied for an entry permit for Jeanette Beer, a former Viennese who had been living in Switzerland since 1938. Jeanette had secretarial qualifications and Bill guaranteed that he would employ her and ensure that she was not a charge on the state after her arrival. Normally, such an application would have a reasonable chance of success as Australia had embarked on a massive immigration program. However, there was a problem with Jeanette’s application – she was a Jew. It is not widely known but from mid-1946, Australia had a quota for Jewish immigrants. In any passenger ship bringing migrants, no more than twenty-five per cent could be Jews. In 1948 the quota was extended to planes. The definition used was a racial not religious one. The NSW representative player, John Makai, for example, came from a Hungarian family with Jewish origins that had been Catholics for some generations. However, when he tried to bring his brother over after the war, he was classified as a Jew for quota purposes.

There were a number of other restrictions on Jewish immigration in the post- war period, driven in large part by Government concern that public opposition to Jewish immigration would bring down its broader immigration reform of bringing in large numbers of non-English speakers and displaced persons from Europe, which was already treading on thin ice in terms of public acceptance. In Jeanette’s case, it was noted that she was a refugee from Austria, the current and future status of which was still very uncertain, being then under Soviet occupation. It was agreed that processing of her application would be deferred until peace treaties had been completed that would clarify whether Austria had obligations to take back its Jewish refugees from the Nazi era. There is no record of the application ever being processed again.

After Competitive Bridge

Perhaps, due to the influence of Tim Seres, Bill owned a racehorse that had some success at Randwick but, outside of work, it does not appear that there was much time for anything but bridge. When he stopped playing competitively he moved his energy to administration, teaching and directing.

He ran the NSWBA, as Mike Hughes recalls, with an iron hand. You needed permission from him to progress from other weeknights to the Monday night field. He also allocated seating. One strong player was believed to give himself an edge by listening and perhaps looking at the table behind him where his boards were coming from. In Grosvenor street premises players moved between rooms – so he always allocated the player in question a table that got its boards from a different room, well out of earshot.

He had been involved in the committee of the NSW Bridge Association since 1946 but when the administrative system of the Australian Bridge Federation changed in 1961 he became Treasurer. (Previously, each state ‘hosted’ the ABF for a year and the office holders changed every year with the host state.) He was Treasurer from 1961-68. He promoted bridge lessons, taking out advertisements in the Sydney Morning Herald, did the directing at the Sydney Bridge Club and directed and supported in other ways regional congresses in NSW. He donated the Schaufelberger Cup.

He died in September 1972, perhaps fittingly while conducting a bridge cruise on the Orana. Following his death, the NSW Bridge Association organised as a tribute, an exhibition match between a team of international representative players – Tim Seres, Roelof Smilde, Winsome Lipscombe, Dick Cummings and Mary McMahon – and a youth team composed of Bobby Richman and Di Leathart (Smart) of Melbourne and Ted Griffin and Alan Walsh of Sydney. One of the great attractions was the use of the Bridgerama – then a major novelty with only a few sets existing in the world.

Bill had no children but, as he had all his life, his mentoring ensured that there were plenty to follow and remember him. The players he had brought along dominated Australian bridge for some time to come. He had for some time been supporting and encouraging Ian McKinnon to take over as Director of the NSW Bridge Club. His wife Greta continued to work with the NSW Bridge Association as de facto manager of the club’s Elizabeth Street premises. She collected table fees, did the secretarial work and organised events. His teaching and mentoring legacy was to be found in Australian teams for many years later.